The Midwives Book

| Title | The midwives book, or, The whole art of midwifry discovered.: Directing childbearing women how to behave themselves in their conception, breeding, bearing, and nursing of children in six books |

|---|---|

| Contributor(s) |

Sharp, Jane

(author) |

| Year | 1671 |

This is a visualisation taken from Voyant Tools which shows the most common words and concerns of this text and how it pertains to the female body. We can see evidence of the idea of female seed, as well as the importance of the womb in medical literature. Pain features, as does references to humoural theory. Contemporary uses of language for parts of the body also feature (‘yard’, ‘stones’).

Historical Context

Our second female authored source is The midwives book, or, The whole art of midwifry discovered.: Directing childbearing women how to behave themselves in their conception, breeding, bearing, and nursing of children in six books by Jane Sharp (dates unknown) dated to 1671. Specifically addressed in the prologue as “To the Midwives of England” (Sharp, 1671, n. pag.), Sharp dedicates the text to women in recognition of the continuous need for content intended for a female readership. Hellwarth described The Midwives Book as the first English midwifery manual penned by a woman (2002, p. 58). Much like our earlier texts, Sharp compiles the works of others, claiming to have interacted with many extant translated medical books in order to succinctly provide information which would accompany her own experience as a midwife.

Jane Sharp herself is an enigma. Some scholars believe she did not actually exist, and was instead a pseudonym of an anonymous author, either male or female. There is no record of a Jane Sharp working as midwife in England around the time of publication. Here in the digitized source, we can see a dedication to an Ellenour Talbutt, complicating the matter of Sharp’s existence as she names the former as her “much esteemed friend”. Whether this is a marketing ploy of the publisher is uncertain. There is little available online about either women, so the attribution of this text to a real midwife is questionable, although there are many women in history for whom we do not unfortunately have a record, so it perhaps this gap in the historical record is not so unusual.

This text copies and borrows heavily from other contemporary sources. These acts of harvesting are evident, as every few sections of a chapter seem to repeat the information previously listed, implying that perhaps Sharp did not edit out redundant passages, and instead directly translated passages from multiple texts and placed them under the same chapter. Ideas about humoral theory and citations of Classical scholars are also present within The Midwives Book. This compilation also contains contradictory information. Early in the text, Sharp describes the anatomy of male and female bodies in relatively modern constructions, but later, possibly arising from her translation work, statements about the vagina falling out to create a penis appear, which is a remnant of the Galenic one-sex reversal theory. This theory had already been disproven in Italy a century earlier, which shows us that Sharp extracted information from texts written in the 15th or 16th century, raising an issue for modern researchers. This contradiction is also troublesome because while southern Europe was advancing towards more logical, scientific findings, the people reading Sharp’s book in England would have been taking in information that was outdated by centuries.

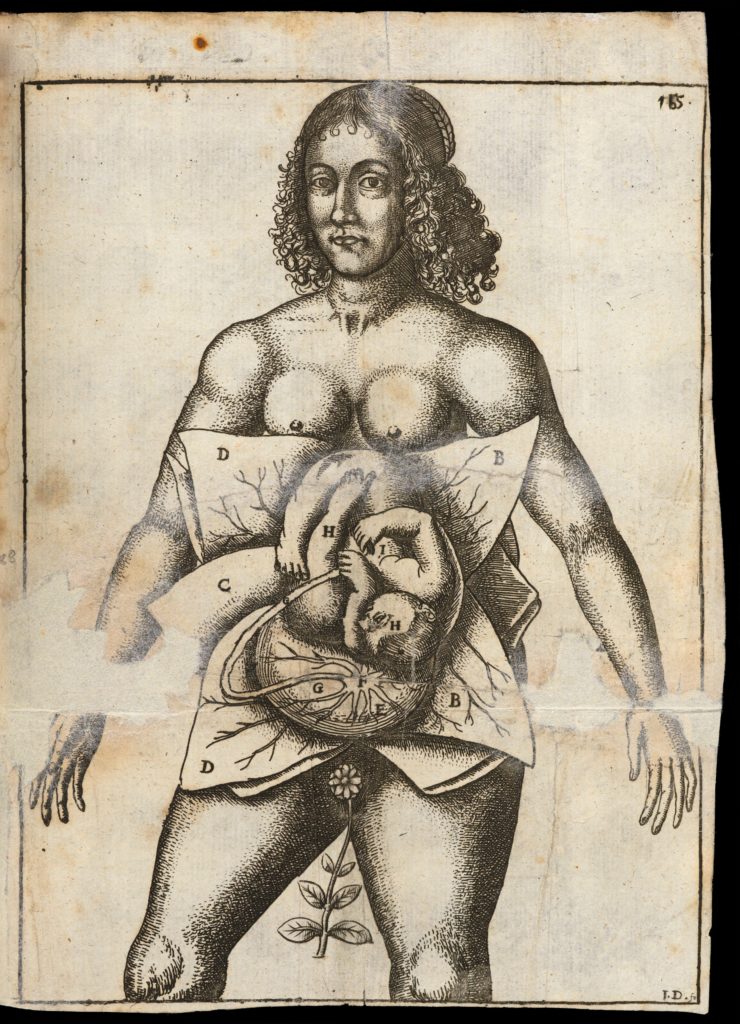

This image, hosted by the WellCome Collection, shows the labelled female body with a key printed opposite the illustration to describe the body parts.

In this image from Sharp we see both a physical and metaphorical flower, as well as the implication of a woman’s fertility of her garden. ‘Flowers’ was a term for menstruation used in the 17th century. Covering the genital area with a flower is also potentially a way for the publisher to avoid any accusations of impropriety in displaying the naked female body in vernacular texts, which had a much wider public reach than Latin medical texts.

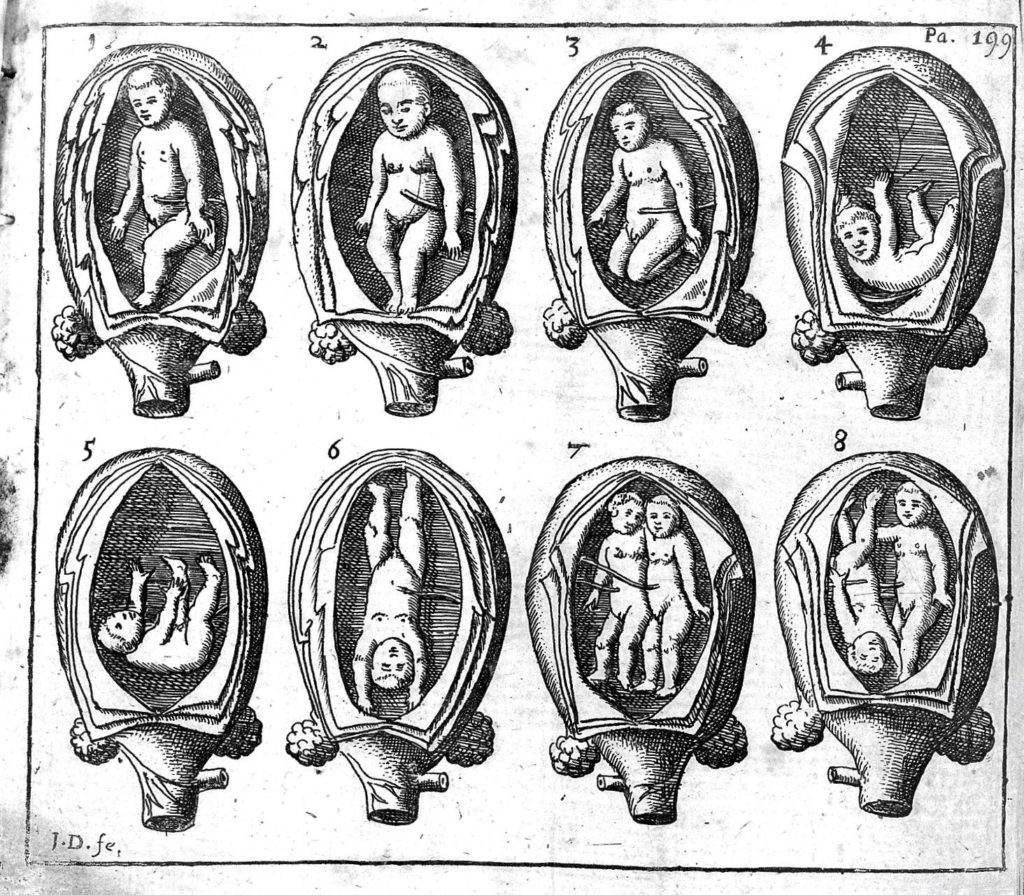

These images show how practitioners understood differences between twins forming in the womb. The range of motion of the child is also depicted.

The internal female body remains murkily understood; the ovaries should be above the neck of the womb and are in reality, much further away, connected to the womb via the Fallopian tubes.

Source

We consulted one version of this source which also served as our .txt data file, the 1671 transcribed edition hosted by the University of Michigan. There is also a digitised version of the text hosted by ProQuest, which we were able to access using institutional logins, but which is not available via open-source, so we prioritised the text file.