Pregnancy/Gestation

“How a woman must governe herself the nine months she goeth with child”

(Guillemeau, 1609/1635, p. 27)

An interesting aspect of our research was the notion that the length of pregnancy was uncertain and fluctuating, starting as early as 6 months and lasting as late at 13 months. For our modern perspective, this may come as a shock - how did people not know how long it took to grow a baby? When we factor in the uncertainty people had over whether they were pregnant until obvious symptoms appeared, the frequency of premature births, and the intense influence of Classical theories, the flexible birth length is much more evident.

The length of pregnancy was most easily understood to last around nine months, but our sources never quite agree on whether it was supposed to last up to nine months or whether that was merely the average time of gestation. For some authors who held to Classical teachings, a seven-month pregnancy was seen as the proper time to give birth, unless the child was not ready, in which they should be born at nine months, but never at eight months since they thought the child would not survive long after. The explanation as to why a child born at eight months would not live is a matter for debate. In several of our sources (Culpeper, 1651/1662; Sharp, 1671) we find the same explanation that the child who tries to be born at the ‘perfect’ seven months mark but is too weak to break their mother’s membranes, would not have recovered enough strength a month later to try again, whereas they would have garnered this strength by the nine month mark. If, however, they were able to break through in the eight month, all of their strength would have been used in being born and they would die soon after (Culpeper, 1651/1662; Sharp, 1671). We see this belief with our earliest source in The Byrth of Mankynde:

The due season is most commenlye after the .ix. moneth or aboute .xl. wekes after the conception / althoughe some be delyuered sometymes in the seuenthe mo∣neth / and the chylde proueth verye well. But such as are borne in the eyght moneth / other they be dead before the byrth / or els lyue not longe after / as the noble medicine Auicenna doth testifye.

(Roselin, 1532/1540, n. pag.)

Another mention alongside Classical beliefs were fables of women having children at the twelfth month. Du Coudray (1759) even quotes from Trois livres (1563/1572) about how children should be born at whatever time they needed to be born in order to be considered full grown. The nutrition that the mother ate and gave to the growing foetus was the leading cause for such late or early births. Though du Coudray doesn’t say whether she agrees with that herself.

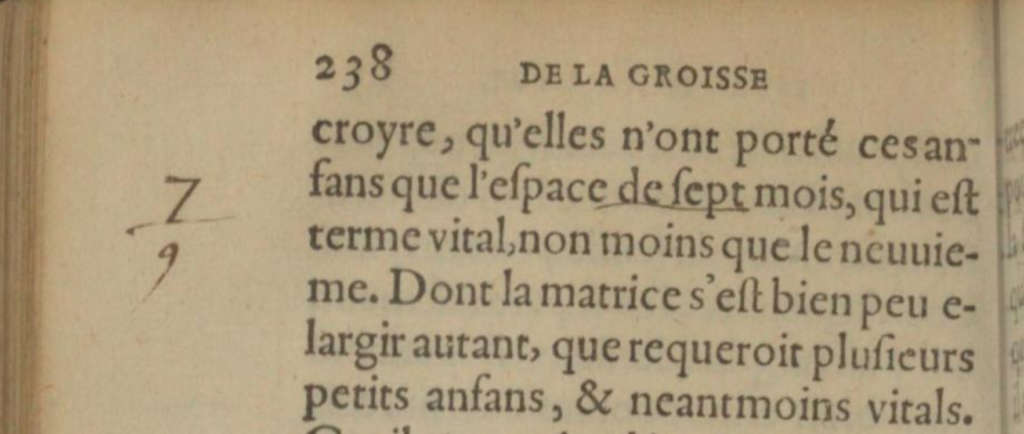

In Joubert’s passage here, he states that a seven month birth is usual in regards to twins, otherwise birth happens at the ninth or “le dernier mois” in regard to whenever the birth comes (1578, p. 238).

We find explicit mention of the pregnancy length in chapter six of The Happy Delivery where women are the focus of the trial. (Guillemeau, 1609/1635, p. 27).

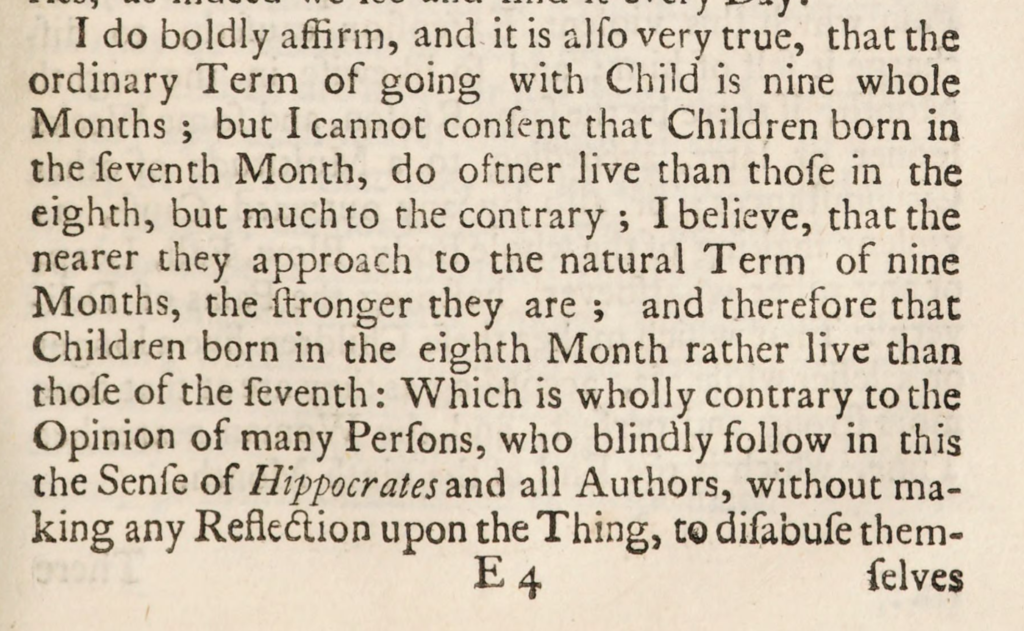

Culpeper and Sharp, who both make ample references to the words of Hippocrates, adhere to the not-eight-months belief but give remedies of how a woman should prepare herself for labour at the nine month as “[t]he ninth and tenth month are the best, saith Hippocrates” (Culpeper, 1651/1662, p. 171). By the end of the 17th century it was generally believed that nine months is the standard time of delivery, as Pechey describes pregnancy to be “a nine Months Sickness,” (1696, n. pag). Most ardently opposed to the Hippocratic teachings was Mauriceau who addressed the beliefs as “contrary to the Opinion of all the World” (1668/1736, p. 120).

In the 18th century we see that nine months is a standard and preferred time of birth, but both du Coudray and Smellie account for untimely births from accidents or multiple children in the womb.

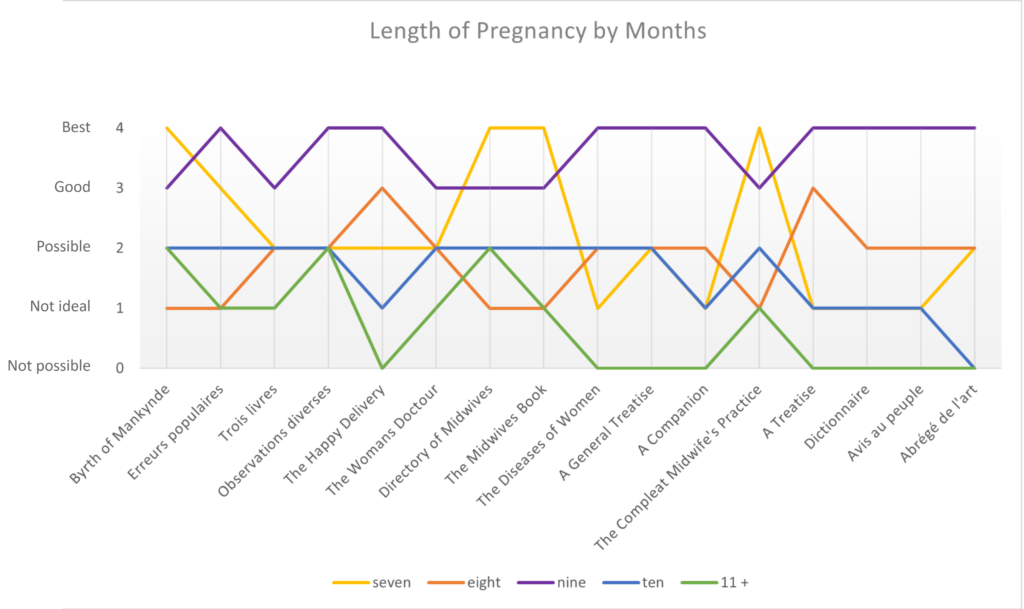

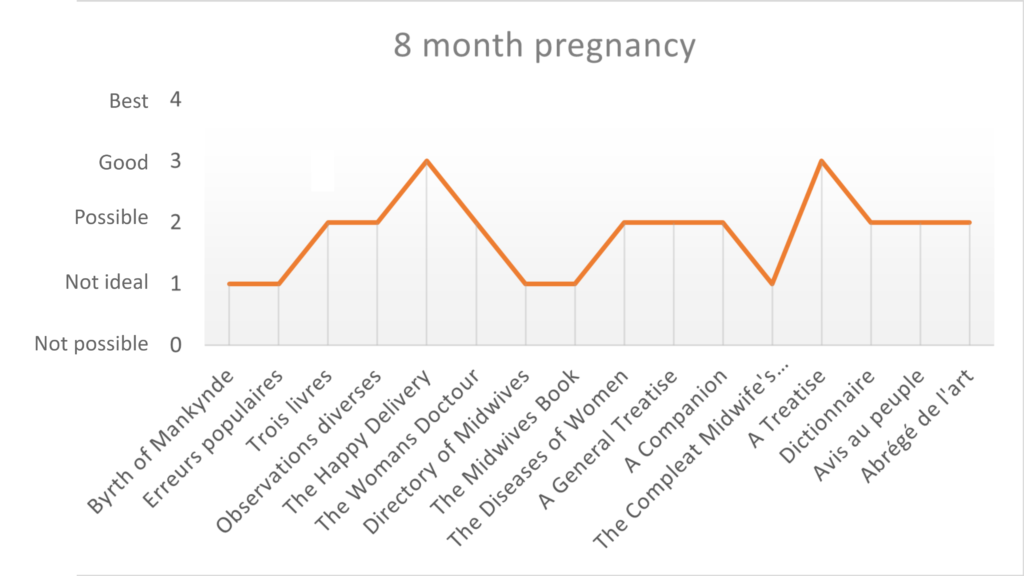

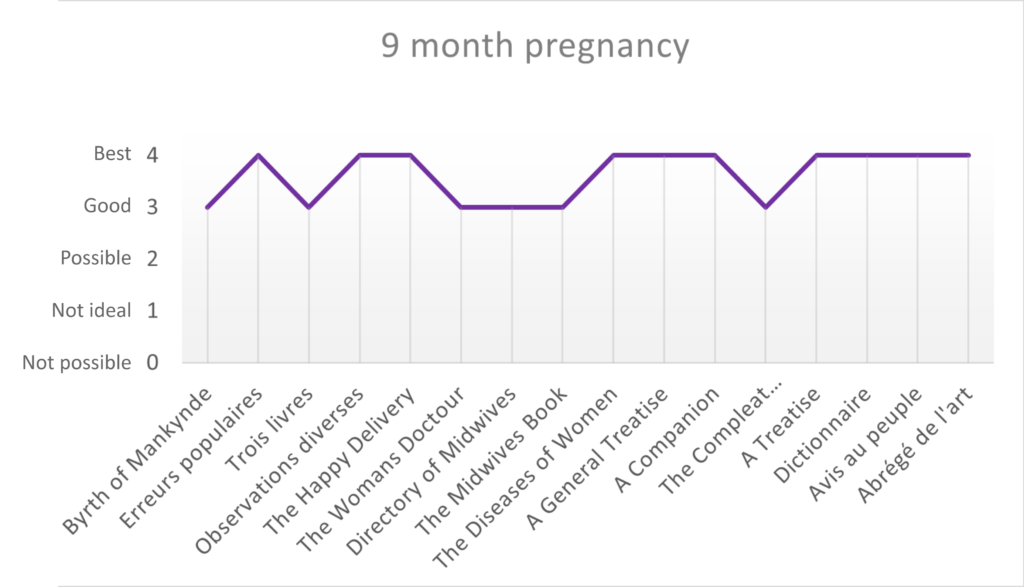

The chart below represents the trends of discussing pregnancy length throughout our corpus. Using a numerical value of 4-0 we show the opinion of the texts and their mention of pregnancy ending at seven, eight, nine, ten, or more months. Barret (1699) retained the idea that pregnancies did not pass the tenth month but considered them not as healthy for mother or child as a nine month pregnancy was.

For individual graphs

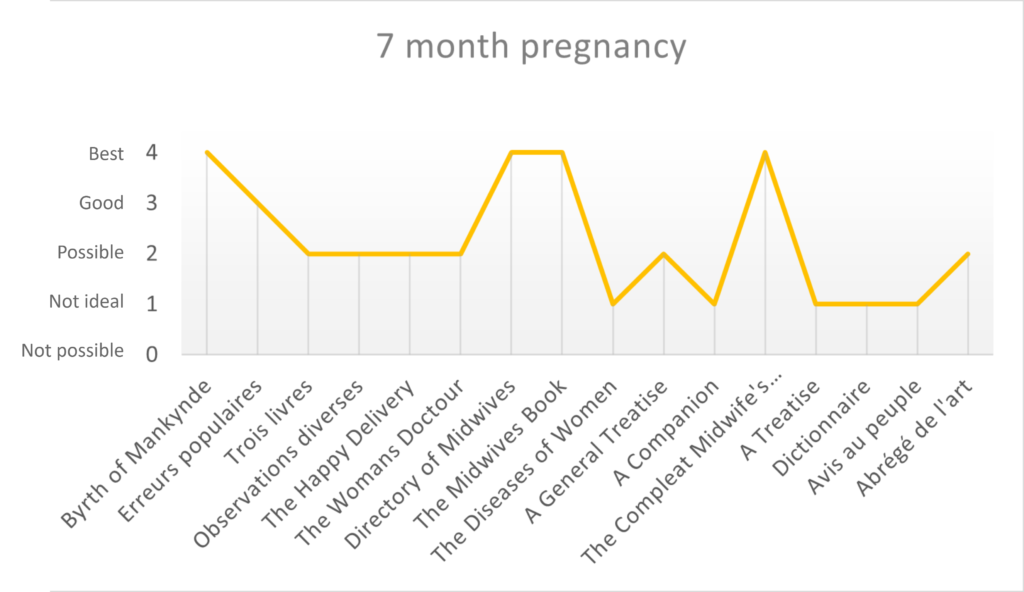

The seven month pregnancy was a leading Classical theory on the best time to give birth. We can see its consistent presence in the 16th and early 17th century until it drops into levels of “not ideal”. The Compleat Midwife’s Practice is an outlier in this regard since it copies much of our early corpus texts.

The eight month pregnancy foetus was thought of as a dangerous and unsurvivable time to give birth and women were instructed to try to retain their labours or eat foods to strengthen the child.

A nine month pregnancy was always considered “good” but not as ideal as the seven month pregnancy until our sources started to leave the 17th century.

Both ten month and more than ten months were possibilities in the eyes of our authors but their presence is mostly used to educate readers as a possibility rather than a commonality. In the later 17th century we see both of their declines and eventual disappearance from being considered possible.