Erreurs populaires

| Title | Erreurs Populaires, touchant la medecine & le regime de santé , par M. Laurent Joubert

La premiere et seconde partie des erreurs populaires, touchant la Medecine & le regime de santé |

|---|---|

| Contributor(s) | Joubert, Laurent (author) |

| Year | 1578, 1601 |

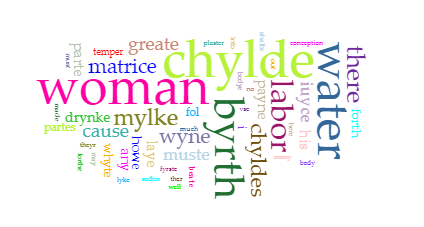

This is a visualisation taken from Voyant Tools which shows the most common words and concerns of this text and how it pertains to the female body. We can see that the woman is central to the discussion and of childbirth. We can also see some of the language used to discuss the body, such as ‘matrice’. Language of birth also includes ‘labor’ and ‘payne’.

Our second source is the Erreurs populaires, touchant la médecine & le régime de santé published in 1578 and written by Laurent Joubert (1529-1582), who became the Royal Physician to King Henry III of France a year later. His text was published in two volumes in French which preserve Joubert’s native Occitan, with colloquial words mixed in.

These volumes underwent numerous reprints which occasionally left out hundreds of pages and accrued drastic editing changes. There is evidence to suggest that Erreurs populaires was controversial at its time of publication.

Some reasons behind this controversy include its vernacular printing and Joubert’s challenging of Classical beliefs, but also its perceived vulgarity. The inclusion of guidelines on how to verify a woman’s virginity, material on men lactating if they were too feminine, and discussions on the health benefits of sexual activity were considered too controversial for the aristocratic and literate ladies, included in Joubert’s intended readership. French society, while cognisant of the need for specific health manuals on the treatment of the female body, was hesitant to allow for graphic accounts of the sexual female body, even as it related to issues of procreation, infertility and copulation.

The 16th century marks a point in medical history where women began to be treated less exclusively by midwives and for those who could afford the luxury, began to employ the services of male doctors. This meant that women were being brought into direct physical contact with male physicians who needed to be mindful of the need to dispute any claim to impropriety by the general reading public who were consuming these new depictions and representations of the female body.

The shift from Latin to the vernacular caters for this shift, as it expands the established market for medical textbooks and manuals. However, Joubert’s authorial intentions are less clear than other texts in our corpus. While some highlight their desire to share knowledge that the reader can apply themselves, Joubert seems to be presenting the ‘learned physician’ as the one source of infallible medical knowledge. While he may criticise women, Joubert’s audience does include women, who he hopes to persuade to choose the attentions of a doctor over a midwife, or at least a more intelligent one. Other male-authored texts, in contrast, acknowledge the large role of midwives in medical care of the female body.

Consult the 1587 edition

Source

We used an earlier source from Gallica, published in 1587, which led us to consider this as a late 16th century when creating our corpus schema. However, we also made use of a later edition, published in 1601 which is consultable for free via Google Books which we used as a searchable text source. The Internet Archive (1578) edition is 684 pages long while the Google Books (1601) edition is 227 pages long, which forces us to find data trends in the later edition which underwent heavy editing after its criticism. Comparing source editions is beyond the scope of our paper, but we wish to bring attention to potential future endeavours.