Birth

“….And when the water begins to be thus gathered, there is no doubt to be made, that the woman is in travaile”

(Guillemeau, 1609/1635, p.92)

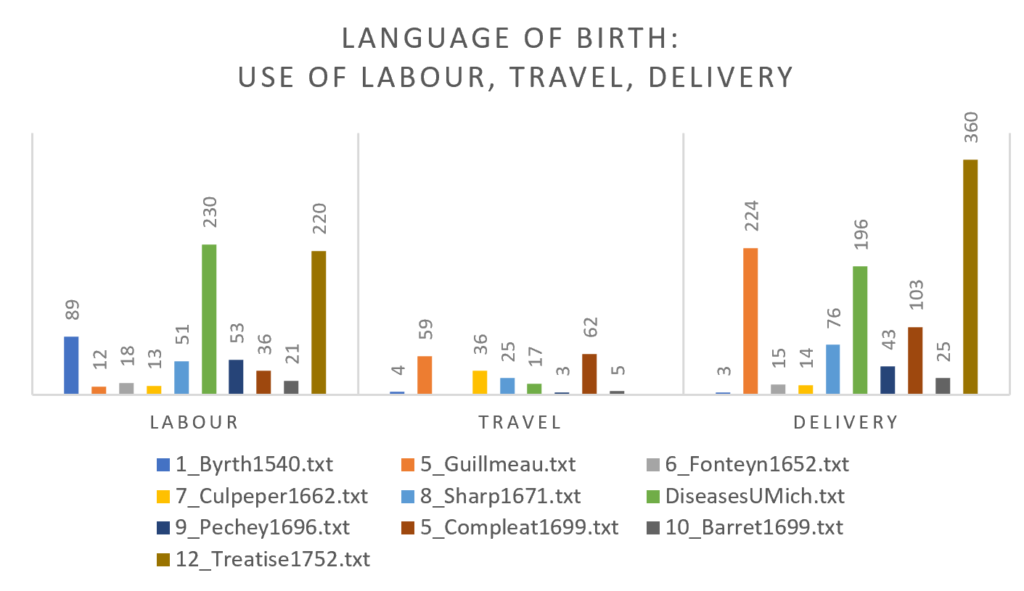

When analysing the language used to describe birth we came across three distinct yet overlapping terms: labour, travel, and delivery.

In our French sources, ‘accouchement’ and ‘enfantement’ are both used to refer to childbirth specifically, the latter being used more frequently in our older sources. ‘Birth’ is the common English term with only Chamberlen using the term “The Reckoning” (Mauriceau, 1668/1672; 1668/1736) as a unique signifier of childbirth. A common trend amongst our sources is the borrowing of precise terms that otherwise had no equivalent in their time. Between our English and French texts, a constant presence was the use of the word ‘travel’ or ‘travail’ respectively, both referring to the moment when a woman is giving birth. Liébault, writing in French, uses both the term “labeur” and “travail” throughout his translation of the Italian text, referring to both the human body at work and the work of childbirth (Marinello & Liébault, 1563/1582). While ‘labeur’ and ‘travail’ both directly translate into the English word ‘labour’, its use in English texts appears rarely and often only in conjunction with other words. The English authors are of major interest here since their translations and reliance on non-English text is what brought the use of ‘travel’ into the English lexicon.

Click here for details on the language data.

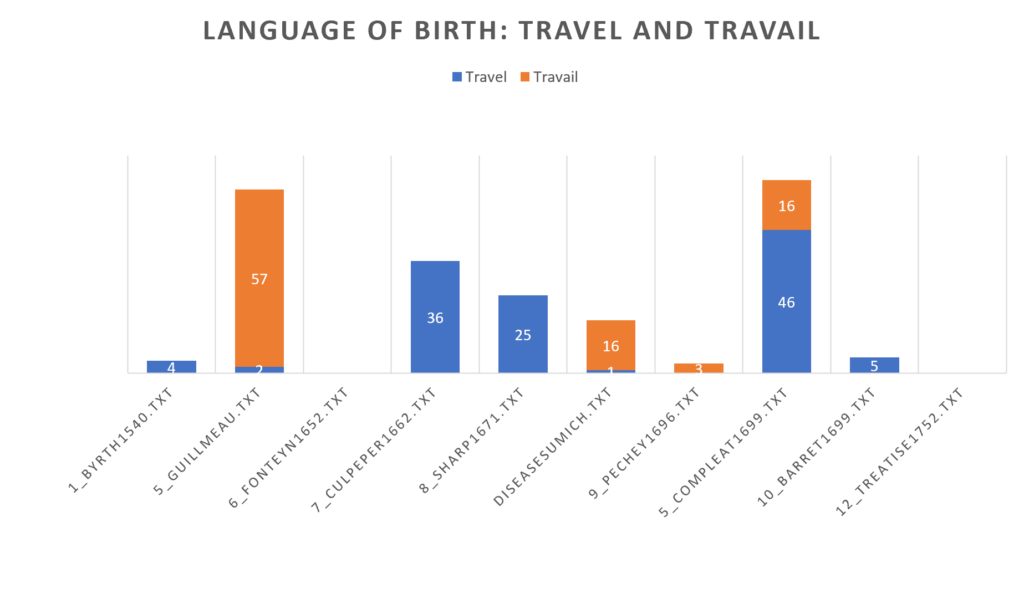

While labour derives from ‘labeur’ we saw no mention of this form in our English texts. The variations of the use of labour were considered in our count, such as: labor, labours, labouring, laboureth, laborer, labourer. Delivery also appeared in many variations, such as: delivered, delievvered, deliverance, deliveyrance, deliuerance. For travel, see the chart below.

In our earliest text, The Byrth of Mankynde, the text introduces us to a passage where Jonas’s translation has applied three terms to refer to childbirth: “and of suche thynges whiche happen and chaunse to the mother in her labor and tra∣uayle / in the deliueraunce of the same” (Roselin, 1532/1540, p. xi, our emphasis). This is also our first appearance of the word ‘labour’. Where ‘labour’ is used more frequently than any of the other terms in Roselin’s text, its use diminishes at the early 17th century. There is a miniscule use of ‘labour’ within the translated edition of Guillemeau’s work, A Happy Delivery as it is, here we see the rise of ‘travel’, written closer to its French form by the anonymous translator. He distinguished the meaning of his chosen words, using “travaille” to indicate the beginnings of labour: “And when the water begins to be thus gathered, there is no doubt to be made, that the woman is in travaile” (Guillemeau, 1609/1635, p.92); and uses the term “delivery” to reference a birth that has come to pass: “That a woman which is delivered with difficulty, and much paine may be helped,” (Guillemeau, 1609/1635, p. 113). Culpeper applies the same meanings to his use of ‘travel’ and ‘delivery’ throughout his mid-17th century text. Sharp also uses ‘travel’ and ‘delivery’ in her text but makes the distinction that the former is about the woman’s work to give birth to the child, and the latter is about the exact moment of the child breaching out of the womb: “Some women have the Chollick at the time they should bring forth a child, which hinders the delivery, and the pains surpass the pain of their travel,” (Sharp, 1671, p. 220). Sharp also uses the term ‘labour’ quite frequently but only to specifically describe the actual physical work and exercise a woman’s body goes through when giving birth or inducing her ‘travels’. Interestingly, the later half of the 17th century sees several of our authors drop the term ‘travel’ entirely. In The Woman’s Doctour, Fonteyn entirely makes use of ‘labour’ but applies the same meaning to ‘delivery’ as Sharp does, as almost every occurrence of the word is formatted as “after her delivery” (Fonteyn, 1651/1662). Chamberlen’s translation of The Diseases of Women makes use of “Travail” and “Labour” as well as “Delivery” which he understood was distinct, as he explained further, “By a Delivery we understand either an Emission or Extraction of the Infant at the full time, out of the Womb” (Mauriceau, 1668/1736, p. 117). In 1699 we are introduced to Barret’s guide for midwives in which he makes use of all three words of childbirth in his utmost economically elegant metaphor:

The Labour of Delivery, is the only Port, but full of dangerous Rocks. The Woman, after she has arriv’d at the desired Port of Delivery, and has disengag’d her self of her Loading, has yet much need of help to defend her self against a great many In∣conveniencies, which may ensue upon her Travel.

(Barret, 1699, p. 37).

Subsequently, The Compleat Midwife’s Practice, written by Chamberlayne, also printed in 1699, refers to childbirth as simply “the nearer a Woman is to her time” (Chamberlayne, 1699, p. 72). He sparingly uses the term “Labours” in a seemingly proper voice of clerical respectability. The term ‘travel’ is not found in any of our English sources after the year 1699.

Click here for details on the language data.

All variations of the word for ‘travel’ and ‘travail’ were used such as: travaille, travels, travails, trayvels, trauels, trauvayle, traueler, traveler, traveling, trayvling, .

‘Travail’ was found mostly in the translated editions of originally French texts, such as The Happy Delivery and The Diseases of Women. This is also the case with The Compleat Midwife’s Practice where most of the content inside is a replication of Bourgeois’ later works. While the Byrth of Mankynde is an outlier for its 16th century presence, and A Treatise for its 18th century presence, Mauriceau’s work is the obvious 17th outlier as he speaks on birth the most of any source and, through Chamberlen’s translations, uses both terms interchangeably.