A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Midwifery

| Title | A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Midwifery |

|---|---|

| Contributor(s) |

Smellie, William

(author) |

| Year | 1752 |

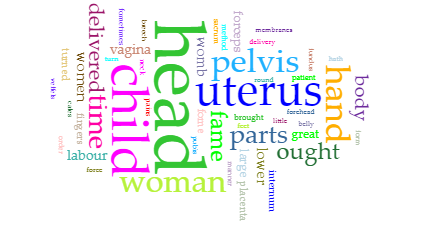

This is a visualisation taken from Voyant Tools which shows the most common words and concerns of this text and how it pertains to the female body. The appearance and prominence of ‘uterus’ is an important shift from previous sources, as well as the appearance of ‘pelvis’. Other terms are important such as ‘membranes’, ‘placenta’ and ‘belly’. Smellie refers to the forceps, a tool whose place in in midwifery he helped to establish following its earlier invention.

Background to the text

To start the 18th century we jump to 1752 with William Smellie and his influential text, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Midwifery. Published in three volumes over the course of ten years, he worked on the text while teaching about midwifery. The text is informed by the compilation of patient notes and case observations with precise medical terminology assigned to each part of the female body.

Born in Scotland in 1697, Smellie trained as a medical practitioner, ultimately turning towards midwifery and obstetrics. He had no medical degree nor a license to practise, but he was so intent on saving children from difficult births to that point that he travelled from school to school, across England and France, and tried every tool and method that was sold to him until he returned to London and started his classes on midwifery in 1742.

A Treatise is our most medically sound text and lacks the reliance on Classical voices as we have previously seen. However, Smellie does state that some writings of Hippocrates were of worth and laments the fact that “the assistance of men was seldom solicited in cases of Midwifery” (1752/1974, p. lxxi) during his ancient era, highlighting A Treatise as a departure point in our sources, where women are subsequently deemed secondary to the practice of obstetrics.

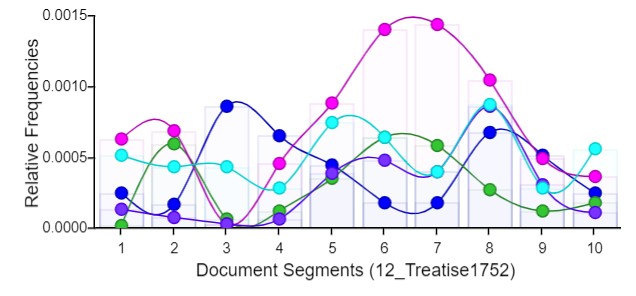

This visualisation from Voyant Tools demonstrates how discussions of the ‘head’ of the child peak towards the mid to end section of the text, as Smellie details how midwives should act in difficult births, where often the emerging child’s head is either not where it’s supposed to be (a breech birth) or else the head is what needs to be grasped (safely) by the forceps, as seen below.

“These are obstetrical forceps dating from the mid 1800s, made to a design inspired by the great pioneer of obstetrics, William Smellie. They were intended to grasp the head of a baby and help ease it out during a difficult birth.”

Unknown maker. (1701-1800). Smellie-type obstetrical forceps, England, 1701-1800 [Leather; metal]. In Smellie-type obstetrical forceps, England, 1701-1800 [co94674]. https://jstor.org/stable/community.26439998

“They were greased with hog’s lard so the obstetrical forceps could be inserted into the body easily. Obstetrical forceps gripped a baby’s head during difficult labours to help delivery. The leather also prevented the alarming sound of metal clacking together. Smellie suggested changing the leather after use to prevent venereal diseases spreading. Ignoring this advice meant they were impossible to clean properly and the leather became a haven for germs. Puerperal fever, a form of septicaemia, was an often fatal infection contracted by birthing women, so using these forceps was potentially dangerous.”

Smellie-type obstetrical forceps, United Kingdom, 1740-1760. Science Museum, London. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Consult the 1752 edition

Source

We consulted one version of this source, a digitised 1974 facsimile of the first edition from 1752 hosted by Google Books, which also served as our .txt data file source. There are also French translations available for this work which we discovered late in the project and thus did not consult them at all, but they could provide other insights into this 18th century text.