Avis au peuple

| Title | Avis au peuple sur sa santé, ou traité des maladies les plus fréquentes |

|---|---|

| Contributor(s) |

Tissot, Samuel

(author) |

| Year | 1762 |

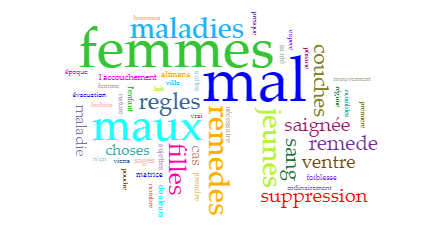

This is a visualisation taken from Voyant Tools which shows the most common words and concerns of this text and how it pertains to the female body. Menstruation is central to this text, with Tissot mentioning regularly ‘regles, ”supression and ‘sang’.

Swiss physicist Samuel Tissot (1728-1797) published Avis au peuple sur sa santé, ou traité des maladies les plus fréquentes in 1762 as a general health manual, following that of Vandermonde in 1760. This is a more generalised text than that of what we have thus far examined, containing only a brief section on health concerns of the female body. However this text is a valuable example of a late 18th century text that occupies the same temporal time frame as the more specialised work of du Coudray. We were able to consult this text in person, which was a valuable part of our research. Although writing in French, Tissot also provides a Swiss perspective to our corpus, allowing us to include a wider European angle to our investigation. This work also continued to be published posthumously into the early 19th century, with the final edition appearing as late as 1803. This indicates the enduring success of work that popularised medical thought.

This page offers some insight into Tissot’s intentions when writing this text; he addresses the depopulation “qui frappe tout le monde” and he desires to play a role in changing how the health of those who live in the countryside is maintained and promoted.

Tissot was also very in touch with the ordinary person being closely aligned with caring for less fortunate patients. He left an extensive written correspondence, with an archive containing letters from patients from all over Europe.

Tissot’s text takes the approach of referring to his own medical experiences.

Portrait du docteur Auguste Tissot, 1783

Huile sur toile, 94,6 x 79,7 cm

© Musée cantonal des Beaux-Arts de Lausanne

The general reader is thus to the fore of Avis au peuple, thus possibly indicating an intended female audience for the sections pertaining to the female body. Included at the end of the book is a list of questions “auxquelles il est absolument nécessaire de savoir répondre, quand on va consulter un Médecin” (Tissot, 1762/2020, p. xxii), with a section specific for women. This further highlights Tissot’s desire that lay people have the vocabulary and medical basis to be able to interact with the profession and consider their own health concerns in a standardised format.

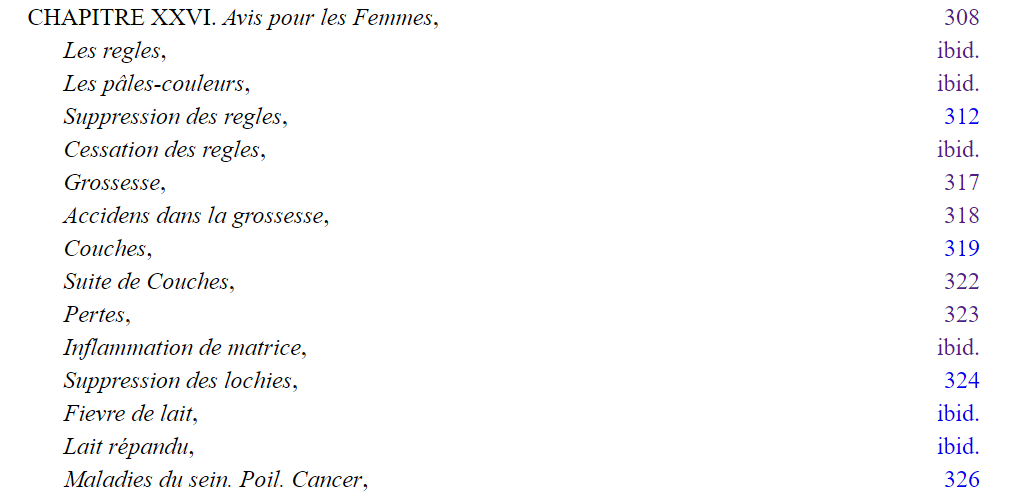

Usefully, Tissot also identifies a framework for considering the female body in medical texts and focuses on “les règles, les grossesses, les couches, & les suites de couches,” (Tissot, 1762/2020, p. 308). This is a departure from the language used in the table of contents of texts from the 17th century, where content is presented by life stages (the virgin, the wife, the expectant mother, the menopausal woman) and health issues arise from the configuration of the female body according to her physical state. Tissot’s text and its treatment of women’s diseases as neat internal processes that can be removed from the physicality of the body, are perhaps evidence of the reality that for doctors of the 18th century, the differences in female bodies can be simplified into mere processes. These processes can be controlled by medicine and male doctors of the 18th century, compared to the notion that it is the female body itself that engenders these differences and thus needs to be brought back in harmony, which is what we see in earlier texts.

In fact, Tissot rebukes women for not taking care of the particularities of the processes of the female body and says that the section on female health “est d’une longueur disproportionnée à celle de l’ouvrage” (Tissot, 1762/2020, p. 317). Galen and Hippocrates are notably completely absent from this text, highlighting the changing focuses of the century and how the developments of scientific knowledge had started to become embedded in the medical canon.

Consult the 1761 source

Source

We discovered this text in the Bibliothèque Grammont of the Centre Diocésain in Besançon, which we consulted in person. We then used the Project Gutenberg eBook source to consult and to manipulate digitally. The 1761 edition is also housed by Gallica, but we seldom refer to this copy except for understanding the typographical layout and for presenting it here.