Abortion/Miscarriage

“[a]borcement or untymely byrth is / when the woman is delyuered before due season & before the frute be rype”

(Roselin, 1532/1540, p. xli)

In the context of our texts, 'abortion' is often referred to often as an accidental, or unintended response of the female bodyto an external set of circumstances, such as injury or sickness of the woman. We can analyse these sections by including an understanding of miscarriage, thus allowing for the temporal context of the word ‘abortion’ to take precedence over the modern understanding.

Framework

The texts on our corpus consider with varying interest the issues of abortion and the management of a woman’s pregnancy. Often, this term does not retain the meaning it has in modern obstetrics, where it is often a premeditated decision to terminate either an unwanted or a dangerous pregnancy. In the context of our texts, it is referred to often as an accidental, or unintended response of the female body to an external set of circumstances, such as injury or sickness of the woman.

Understanding the causes of abortion (miscarriage) in Early Modern Europe

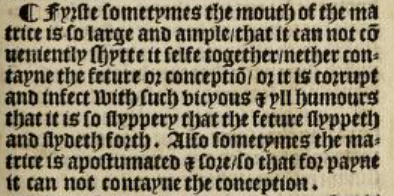

Roselin identifies the cervix not closing correctly after conception as one cause of untimely birth in the early stages of a pregnancy, where “the mouth of the matrice is so large and ample / that it can not cōueniently shytte it selfe to gether / nether con∣tayne the fetuse or conceptiō” (1532/1540, p. xli).

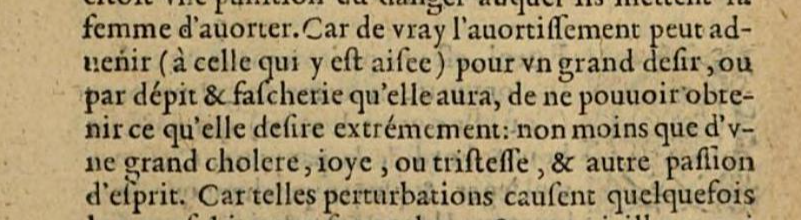

Joubert refers to strong emotions when discussing causes of abortion, writing that “un grand désir […] grand cholere, joye, ou tristesse, & autre passion” (1578/1601, p. 134) can provoke the womb into expelling the mass it holds.

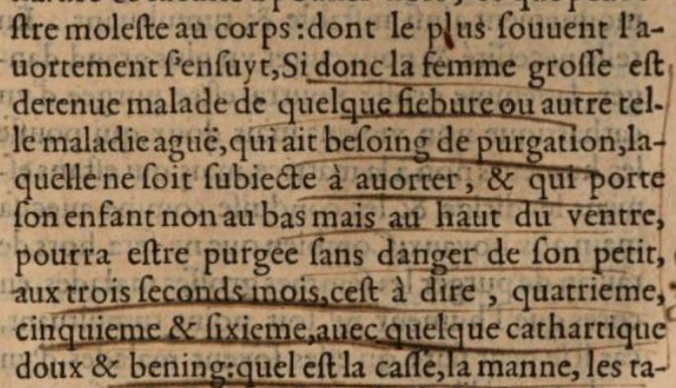

Trois livres advises that women can be purged with the risk of aborting or miscaryying between the “trois seconds mois, c’est a dire, quatrieme, cinquieme & sixieme [mois]” (1563/1582, p. 763).

Guillemeau also pays attention to external weather factors and advises women to avoid “the Northwind [which] also is hurtfull unto them for those winds breed […] trouble∣some Coughs in great-bellyed women,” causing them oftentimes to abort (1609/1635, pp. 18-19).

Fonteyn writes that “we affirme that a woman with childe may be let bloud without any danger of abortion” in certain cases (1644/1652, p. 191).

Culpeper sets the most dangerous time for miscarriage as “the two first months of the conception because then the Ligaments are weak and soon broken” (1675, p. 111).

Sharp writes “when the winter is hot and moist, and the Spring cold and dry that follows it, the women that conceive in that Spring will easily abort” (1671, p. 223).

Vomiting and coughing could also induce a miscarriage, mentioned by Mauriceau who cautions that both of these actions strain the body and “contribute to Abortion” (1668/1736, p. 69).

Pechey recommends that “if the Woman be troubled with a violent Cough she must be blooded in the Arm at any time of her being with Child, for this [the cough] is apt to occasion miscarriage” (1696, p. 100).

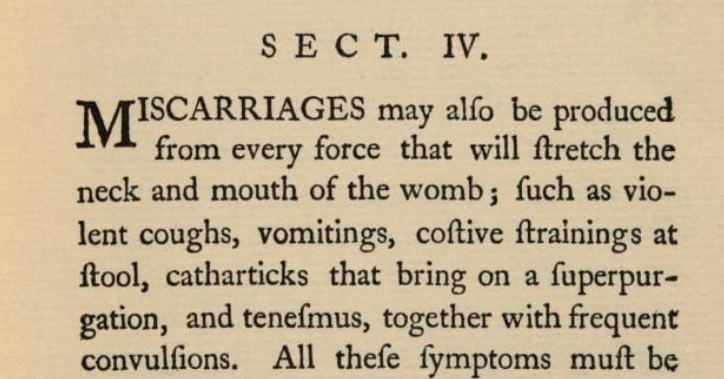

Smellie makes reference to the same disease and its nefarious effects, describing it as an illness that “will stretch the neck and mouth of the womb” to produce a miscarriage (1752/1974, p. 173). This shows the impact illness could have on the pregnant woman and the awareness medical practitioners had of these dangers.

Du Coudray writes that a woman can miscarry as a result of “des efforts qu’elle a faits pour aller à la selle” (1759/1785, p. 45).