Menstruation

Suppression of the Courses [is] when in Women of a mature Age, that neither give suck nor are with Child, the Evacuation of Blood by the Womb, which is Naturally wont to be Monthly, flows seldom, or sparingly, or is wholly stopt,”

(Pechey, 1696, p. 45, our emphasis)

Historical conceptions of menstruation are perhaps the most consistent topic present in the texts in our corpus. This aspect of the female body has a rich literary history prior to the time frame under discussion, with Galen, Hippocrates and Aristotle having written widely on its purpose in, and impact on, the female body. The production of excess blood can be read in relation to Classical humoural theory; as a consequence of women’s weaker composition, they were able to concoct more blood from food than was needed, but they were not as well equipped as man to process this blood into bodily matter or to consume and dispel it through the force of their body heat

Language to describe Menstruation

English sources

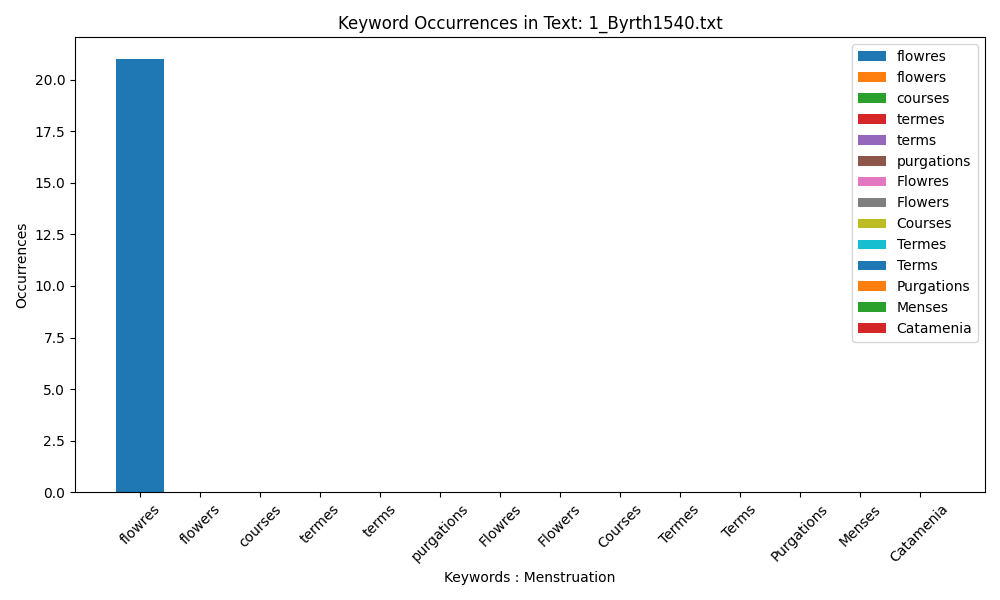

Roselin uses only ‘flowres’ to describe menstruation, with no other term being used. Other argricultural metaphors appear in this source to discuss other aspects of the female body.

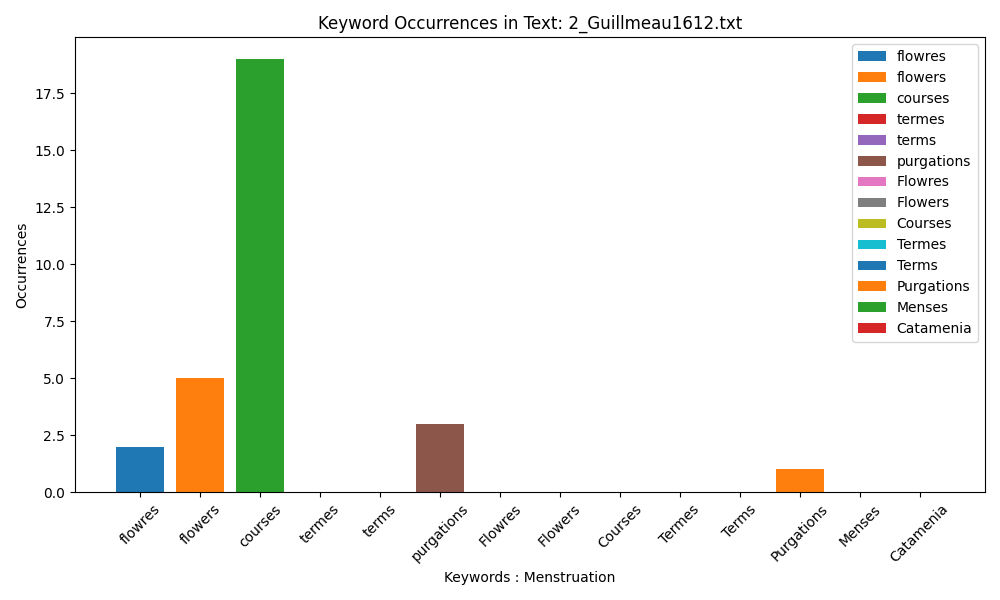

Guillemeau employs a wider range of vocabulary than Roselin, preferring the word ‘courses’.

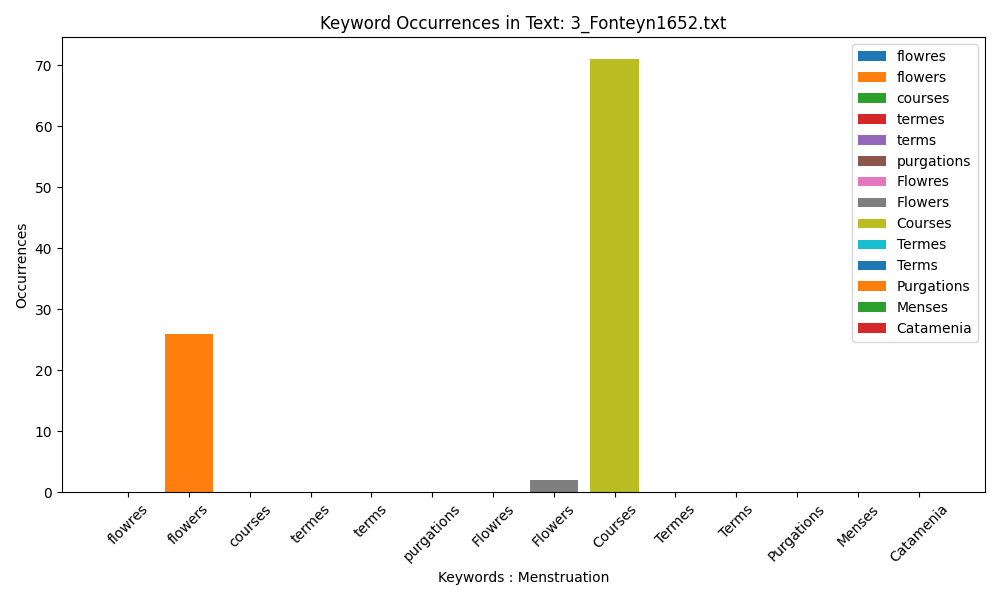

Fonteyn also uses ‘Courses’, but uses the more poetic ‘flowers’ somewhat frequently.

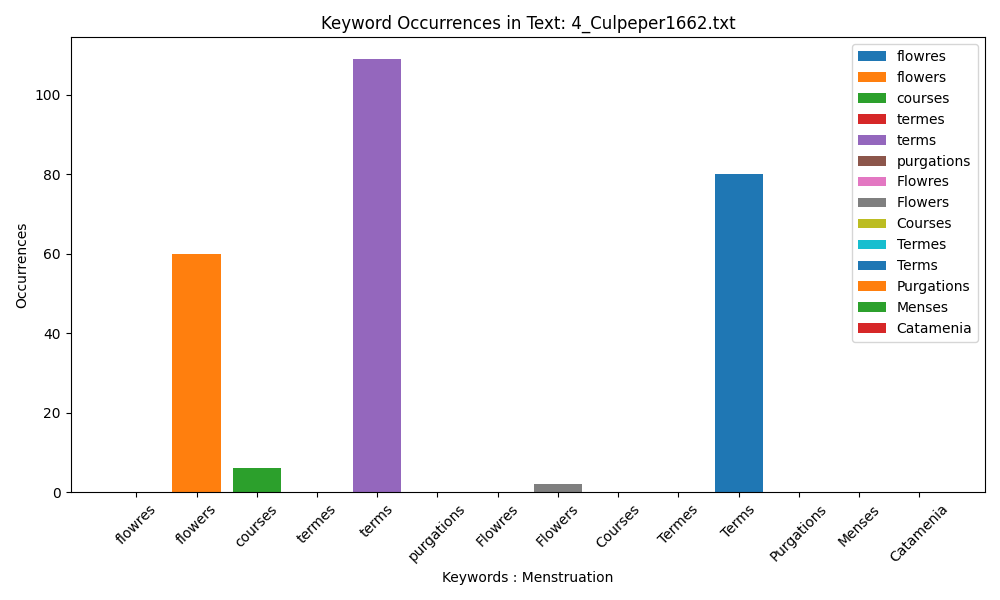

Culpeper introduces ‘Terms’ to the corpus.

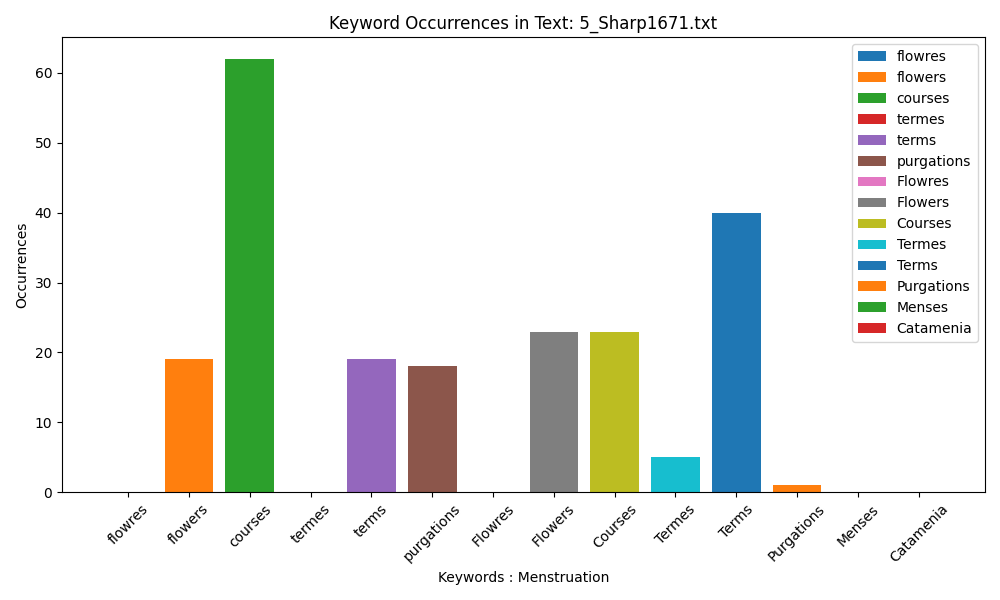

Sharp employs the most varied vocabulary using a variety of spellings. Analysing and comparing these language patterns is possibly an avenue of research into whether Sharp actually existed as a midwife or whether this text is a compilation of extant sources compiled by someone using a pseudonym, as some scholars believe.

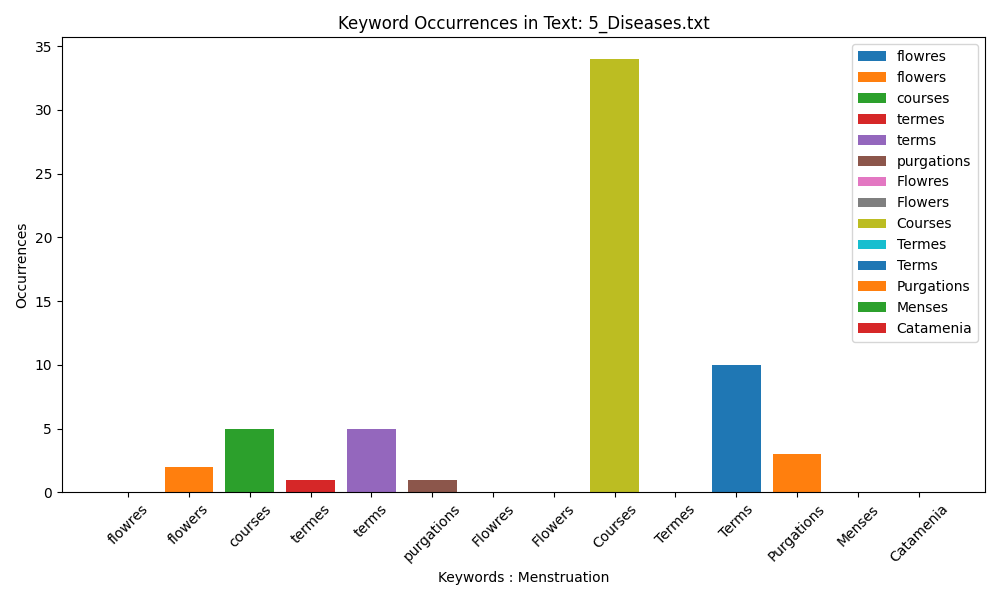

Diseases of Women with Child (1672) displays a strong preference for ‘Courses’, with ‘Terms’ being the second most-used vocabulary term. This suggests the importance of regularity of the menstrual cycle. ‘Flowers’ is used, but this refers only to herbal remedies.

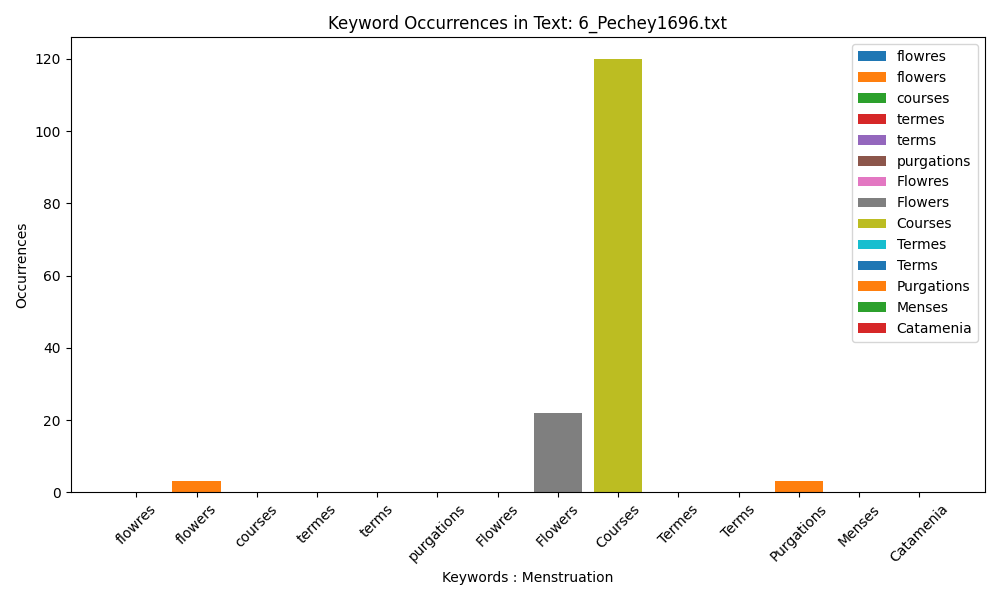

Pechey’s vocabulary is limited and his preference is for ‘Courses’.

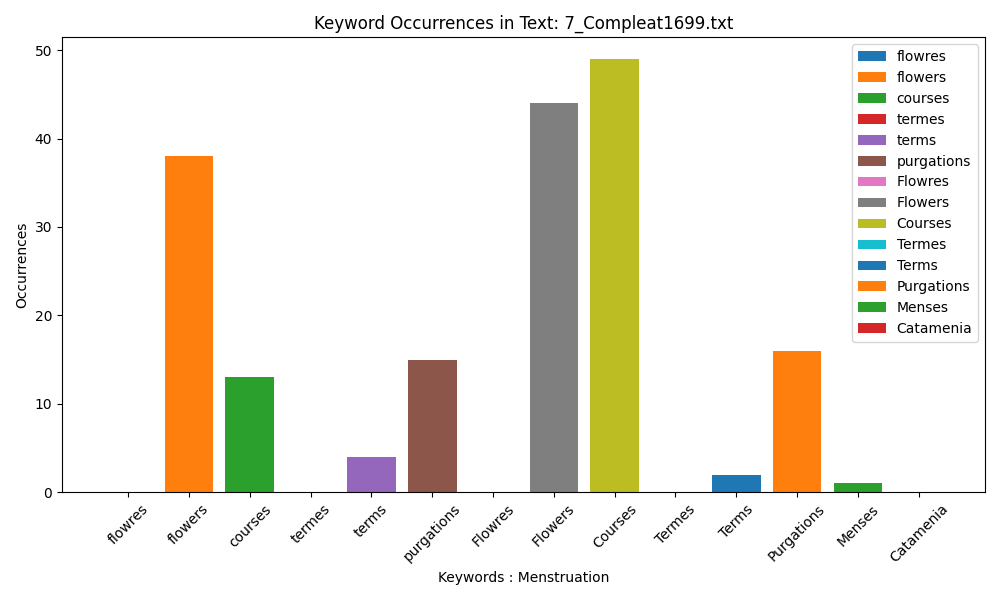

As The Compleat Midwife’s Practice is a compilation text, it makes sense that a varied vocabulary is employed in this text.

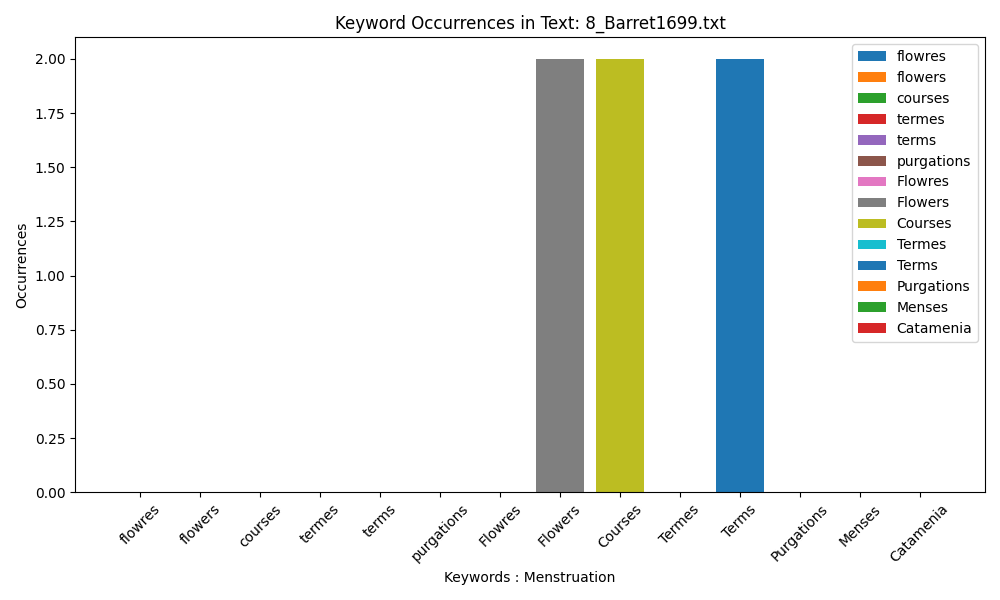

Barret’s use is consistent but he does not appear to discuss menstruation much, as these three terms are used only twice for a total of 6 mentions.

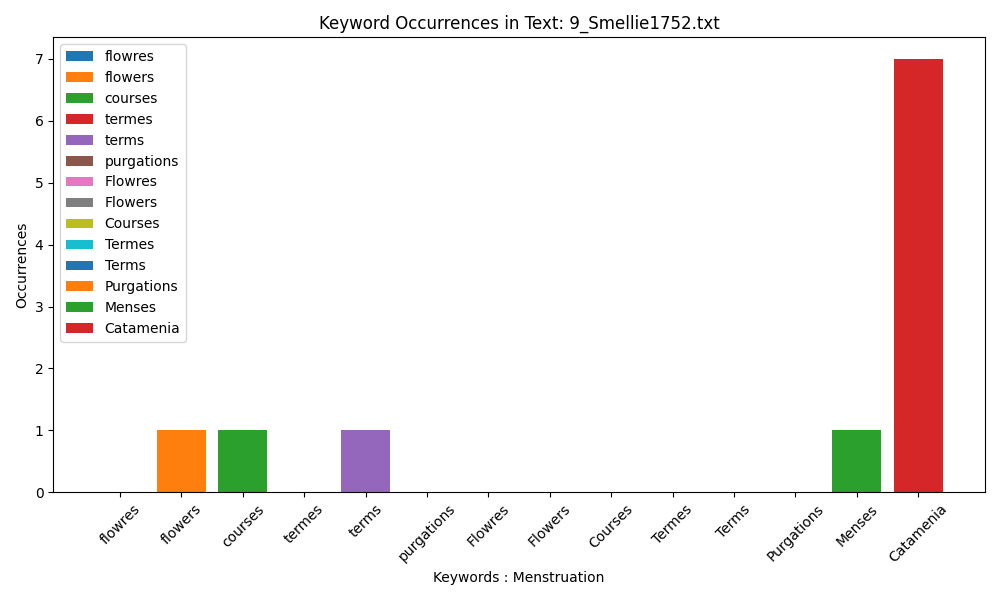

Smellie introduces the more scientific terms ‘Menses’ and ‘Catamenia’ to discuss menstruation, moving towards a more medicalised approach to the female body in the 18th century.

French sources

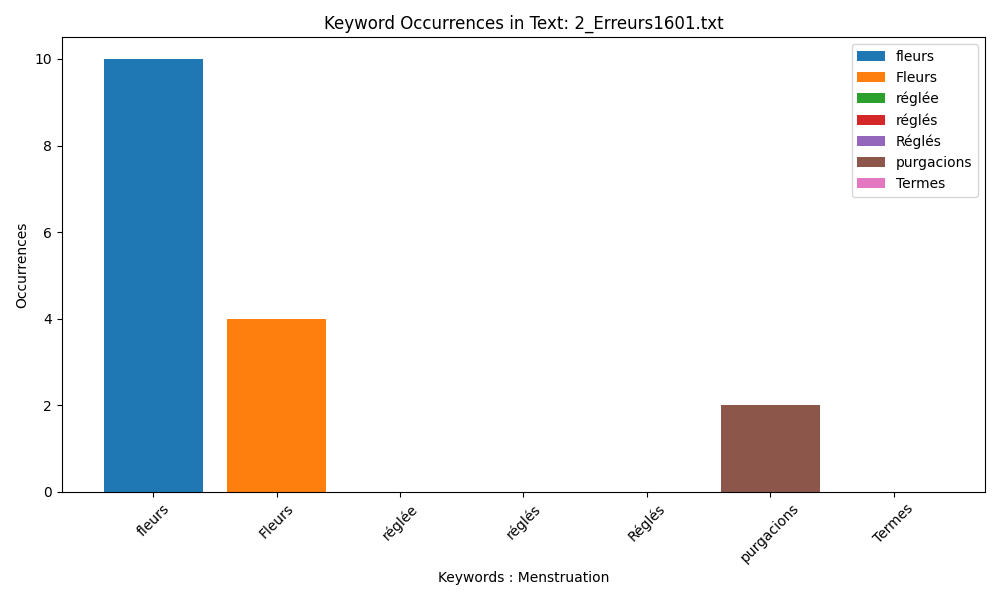

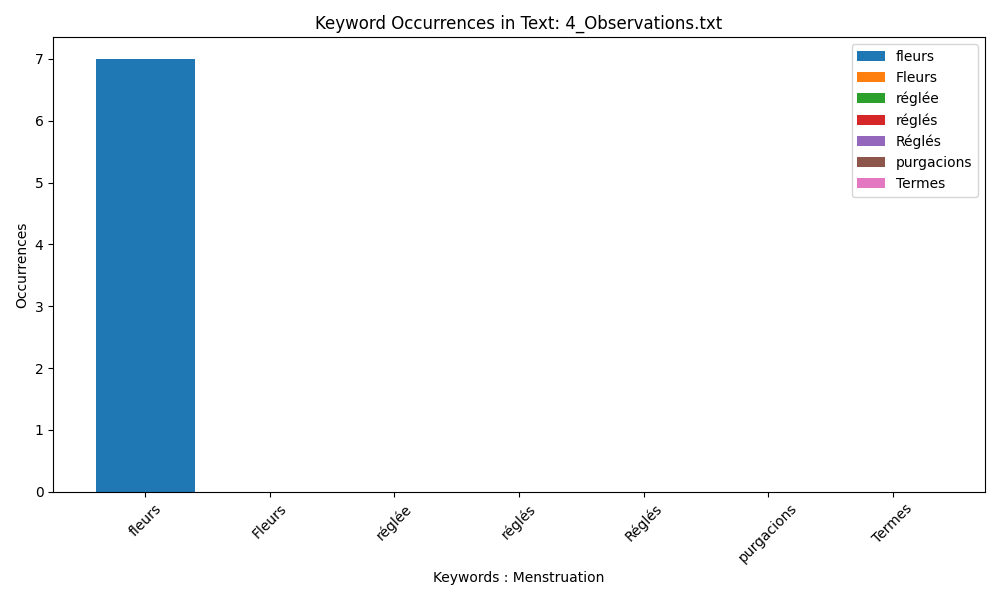

Much like Roselin, the English counterpart to this text, Joubert uses ‘fleurs’ (flowers) and purgacions. Joubert quantifies them as “naturelles” (1578/1601, p. 59

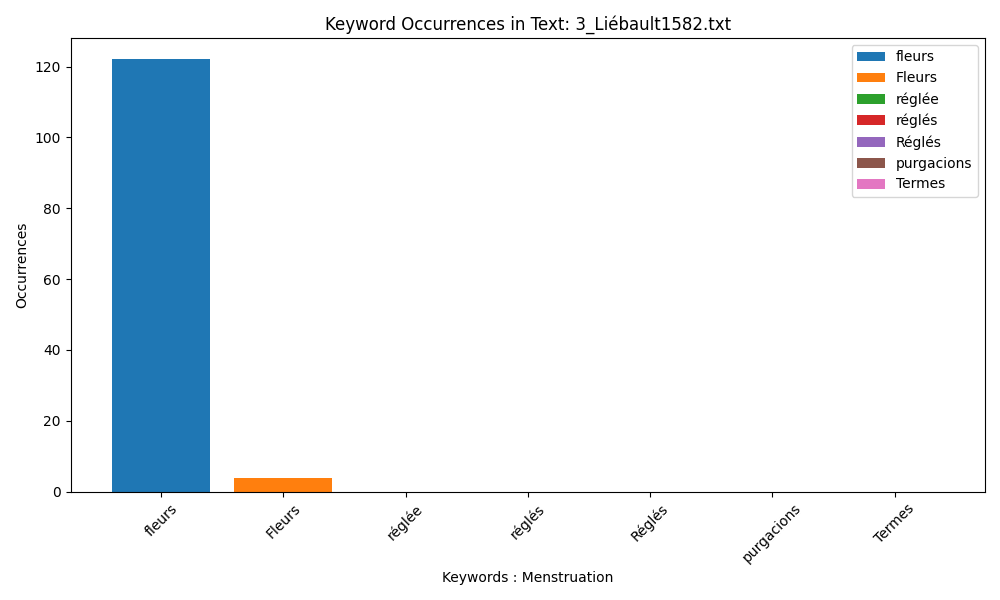

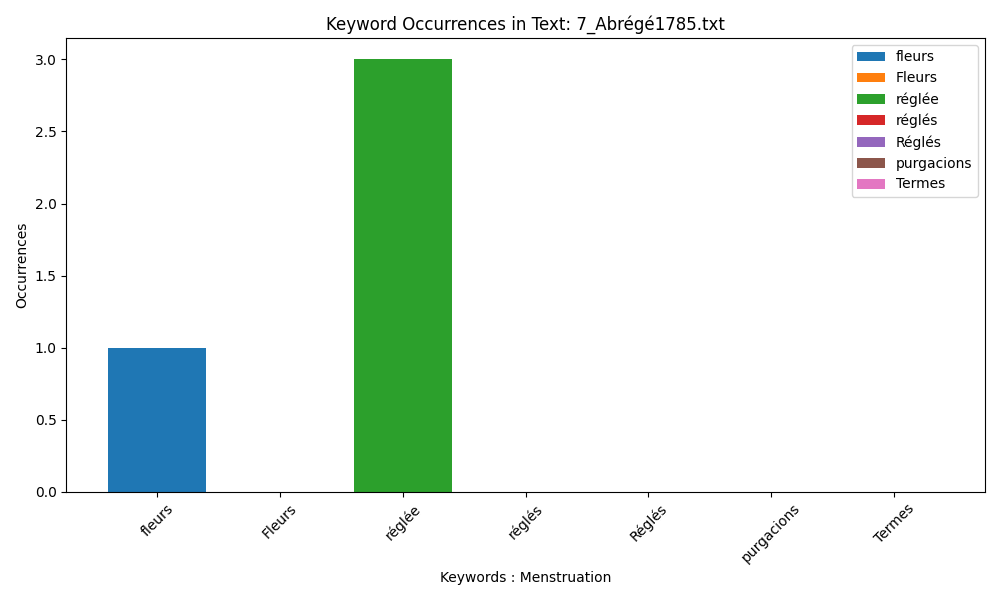

Liébault continues to describe menstruation as ‘fleurs’. Our research of the text indicates that Liébault also uses ‘réglée’; the fact it does not appear here is due to the quality of the text file available to us.

Bourgeois uses ‘fleurs’ in the early 17th century (1609).

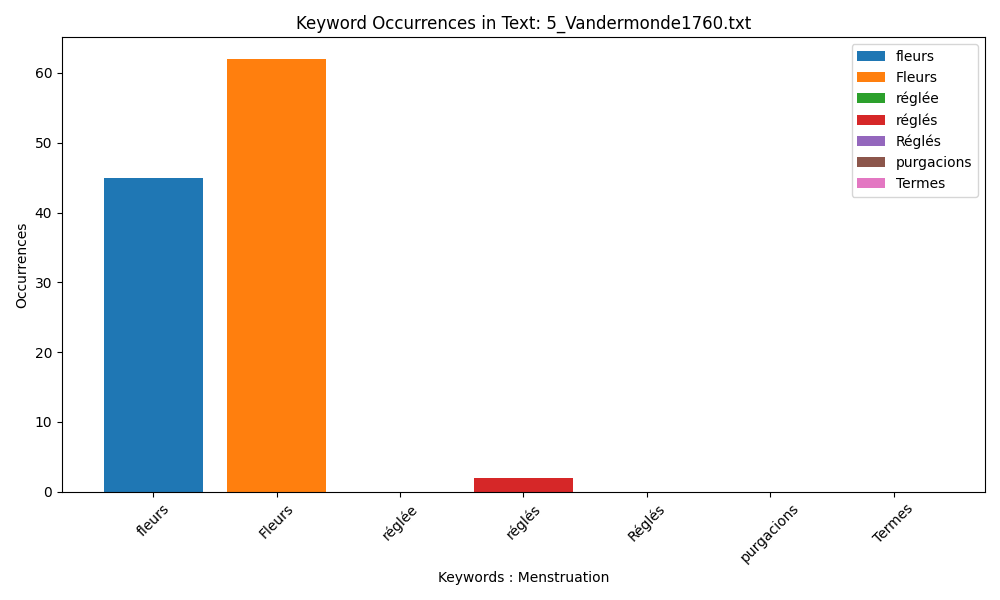

Vandermonde relies only slightly on ‘réglés’.

‘Fleurs’ appears to be used regularly by Tissot; but these are in fact references to herbal remedies. As this text is not dedicated solely to women’s health, it is unsurprising that little space is given to menstruation.

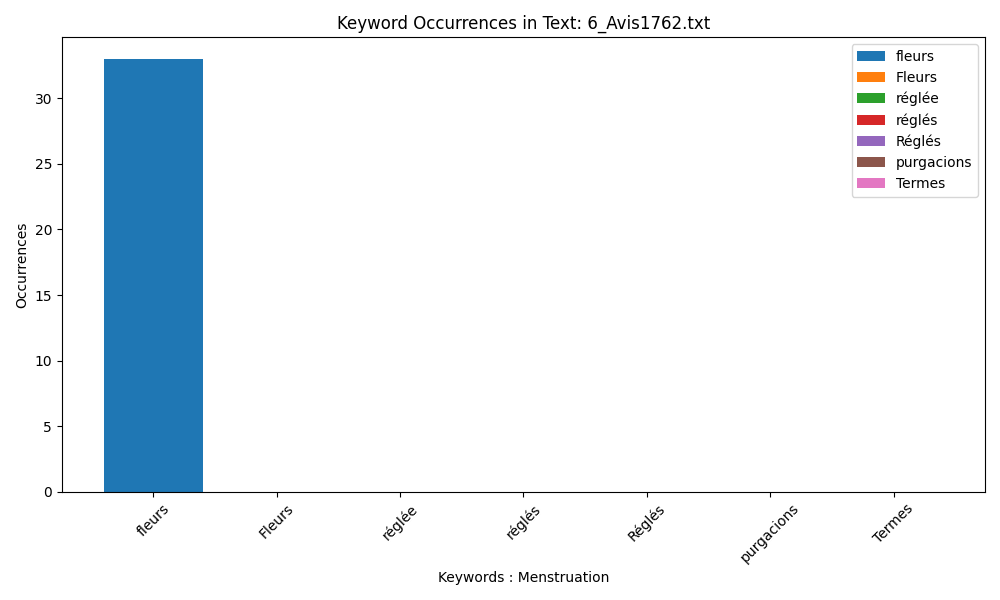

Du Coudray discusses menstruation infrequently, using ‘réglée’ to describe how the woman should be instead of describing the process.

Caveats

Comparing the textual content of old books is a complex process and there are limitations to this method.

The primary sources are of varying length, so the barcharts are not directly comparable in terms of trying to identify which text uses the word the most. Pages numbers could be used to standardise this information, but we worked with text files which did not maintain the page number aspect.

Some words have double meanings; for example some sources do use ‘flowers’ to refer to the menstrual cycle, whereas others refer to herbal remedies. This semantic binary is not captured in these graphs. Where it is documented in the graph, we were able to verify its meaning having read the sources ourselves.

The text files are not all of the same quality; this may affect how the code was able to run and identify the key words. Some texts do not use accents consistently, for example Tissot uses ‘regles’ (without accents), a nuance which we captured in our traditional research.